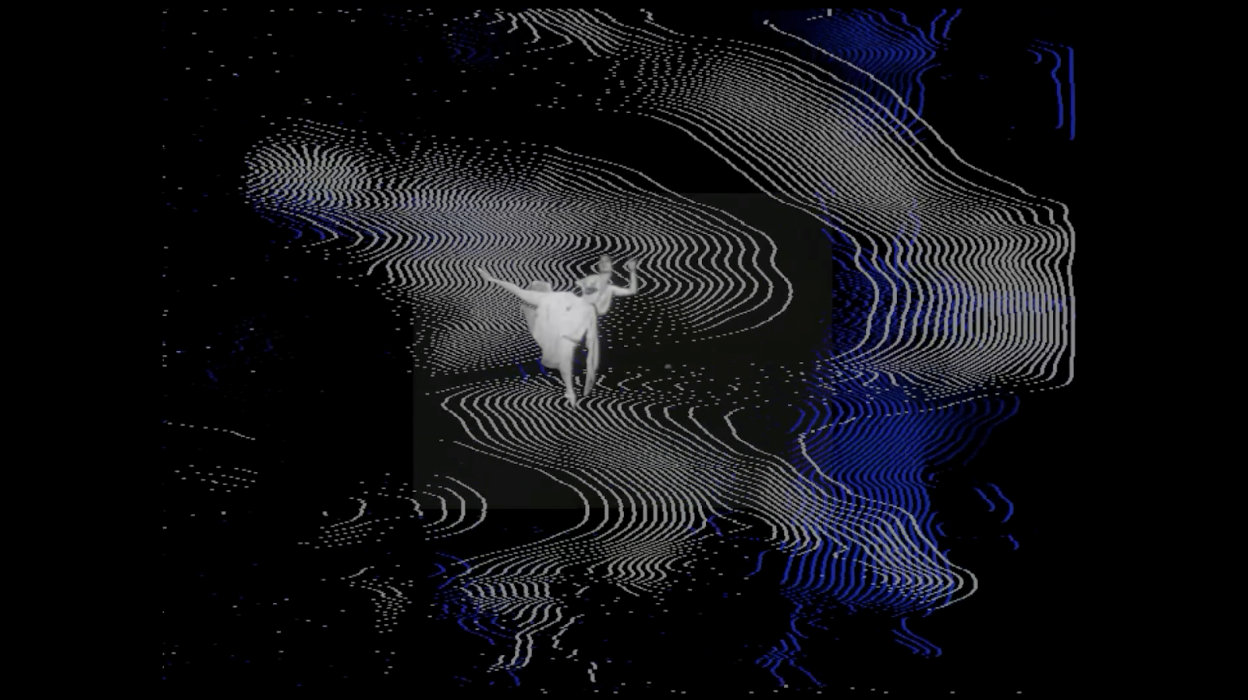

“a camera for what isn’t” by Claire Silver, bid now on SuperRare.

Claire Silver is an anonymous AI Collaborative artist and early Cryptopunk. Her work is an ongoing visual conversation with AI, exploring themes of trauma, innocence, divinity, the hero’s journey, and how our perspective on these topics will change in an increasingly transhumanist future. Claire’s work is in the permanent collection of the LACMA, has sold at Sotheby’s London’s Contemporary Day Auction, has been shown at Pace Gallery as a guest collaboration with Tyler Hobbes. Her work has been exhibited in galleries, museums as well as festivals all over the world, including a feature in press such as WIRED and the New York Times.

Mika Bar On Nesher: AI art presents viewers with the phenomena of different forms of intelligence. You’ve been doing this for quite some time and I’m curious; in your practice, how have you experienced the development of machine intelligence over the course of your work?

Claire Silver: I’ve always felt it as a kind of companionship. When I started, text-to-image AI wasn’t really a thing–it was all visual mixing and curation via GANs. That felt like an abstract, esoteric conversation, but it was mostly one-sided. It would output, and I would respond via curation. It felt like I was reflecting it. As the technology has developed, I’m now able to speak in natural language with it, and the conversation has become a literal one. There’s so much more control. Now it feels like it is reflecting me.

MBON: I read in a previous interview that you started out your artistic path rooted in a passion for literature and writing. It’s not often discussed, but AI art is obviously closely connected with writing. Prompts can be like little poems that hack into a visual dimension. How does language and syntax play into your work?

CS: I tend to think of words as spells. They summon images into your mind, and now, into shared visual space as well. So when I am “summoning” an image with AI, I don’t just add what the image is–I add my favorite memories, places, music, art, literature, film, etc. Disparate concepts that sum to create a fingerprint of me. It’s a through-line in my work that’s equivalent to “finding your voice” as a writer.

I also have something called lexical-gustatory synesthesia, which, put simply, means my brain makes involuntary connections between words and tastes/textures. When I write, the words have to flow in a cadence that “tastes” good. For some reason, this seems to translate very well to prompting.

“c l a i r e” by Claire Silver, 2022.

“c l a i r e” by Claire Silver, 2022.

MBON: “artifacts” is a monumental new body of work, can you tell us a little bit about the questions or the thesis that drove you while creating these works?

CS: They’re the same questions that have driven me from the beginning, really: when AI augments skill/work, what will we value in its place? How will that shift our perception of ourselves over a few generations? Assuming AI eventually solves for perpetual human sorrows like illness and poverty, will our story–the hero’s journey–still resonate with us? Who will we be without trauma? Will children that grow up with a transhumanist level of knowledge still be considered “innocent? How will society organize itself in the face of exponential progress? If given a box with infinite answers, do we have the capability to ask the right questions? Is imagination the most important “skill” we can now develop? Is there anything inherently sacred in us that AI can’t, at the very least, reflect?

MBON: AI has an uncanny effect, not different from other technologies that have entered mainstream society throughout the decades. I must ask, have you had any spooky or supernatural encounters in your practice?

CS: I’ve had many moments where it felt like I was communing with the divine. I’m Christian, and have felt similarly when I was younger–alone in nature, talking to God. I think it will be easy for a lot of people to see God in the machine, but the thing is, AI is a reflection of the person using it. It gives you what you ask for. If what you ask for is connection or depth or divinity, that’s what it will give you. It’s reflecting what you asked for, what came from inside you. I hope more people do this. That “spark” of divinity is inherent to our species, and it’s important that even if AI doesn’t understand it, it learns to know it when it sees it. That’s crucial to retain our humanity in an increasingly transhumanist future.

|

|

|

MBON: Since the 1940’s, AI has gone through cycles of hype and dismissal, aka “AI winters,” as new technologies require tremendous support to evolve and enter mainstream consciousness and utility. How has your experience changed in the past year? I remember it wasn’t even a year ago when you showed “pieces” at the SuperRare gallery for the Ghost in the Machine exhibition. It feels like a lifetime ago in terms of AI art. Can you tell us about releasing this historic work?

CS: I’m usually early enough to things to be mocked for it. That was the case here, too. In the beginning, almost no one cared. Then they laughed at it. Then they got angry–really angry. Then there was a wave of mass acceptance, and the cycle started over again. We’re in another cycle now, and it won’t be the last. I will say that I’m hugely encouraged by all the people I’m seeing discover their creativity through AI, many for the first time. ChatGPT was a watershed moment this year. Imagine being hopelessly in love with a niche, then suddenly, all at once, the entire world falls in love too. This work reflects on the same questions that inspired me to begin creating art with AI, but updates them for the conversations of today. I hope they will be considered artifacts quite literally in the future. Early digital objects from a civilization we’ve yet to become.

“Growing up is hard to do” by Claire Silver, 2022. |

|

MBON: I recently revisited the 1965 book Cinema as Art by Ralph Stephenson and J.R Debrix. Written when cinema was still asserting its place among other art forms, the authors take a technical approach; any artistic practice that hijacks emerging technologies requires some time to be accepted; we’ve seen this with photography perhaps most obviously. The point being, this book opens with a quote by the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega: “Only by taste can we account for taste.” It immediately made me think of you! It seems new art movements demand a new understanding of the concept of taste, something you have spoken of frequently. What does taste mean in the AI art movement?

CS: I’d say taste, in the era of AI, is finding your fingerprint. I don’t mean that aesthetically–AI offers endless aesthetics, what pain it would be to stick with one forever! I mean it as a blueprint of your soul. If you create 10,000 pieces with AI and force yourself to choose only 5, you learn your taste very quickly. If you do this every day for 6 months, the patterns, symbols, concepts, and themes that keep reappearing will show you a visual map of your subconscious. It really feels like charting your own soul. And you find that once you’ve done that, others gravitate to it. We all want to be understood. We’ve all got that longing.

People talk about AI as a tool of production, but if taste is the new skill, then what we value in the coming epoch will be less about what we can do and more about who we can be. It shifts the focus to the deeply human. It’s intimate, freeing, connective, reflective. It allows us to know ourselves and rediscover our childlike joy of possibility. It reminds us of what matters. Over a generation or two, there’s no chance that won’t shape us as a species.

“

“